It’s a difficult world for the faint of heart, for the indecisive, for the misguided, for those who have experienced traumas of relative, substantial proportions. I satisfy all of these criteria, as many of us do. What makes the journey all the more difficult, and perhaps paradoxically so, is my pursuit of knowledge, my conscious efforts to stray from the status quo, my expanding awareness of a phenomenological unity that binds us all as far as the human senses can process and allow.

I disappointed my mother’s next door neighbor yesterday, confiding to him that, although plans were made weeks prior, I would not be able to assist him in moving his king sized bedframe and mattress to my mom’s home – a generous gift as he plans to move out – simply for the seemingly obvious yet bewildering reason that I wish to be nowhere close to mom in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tim, mom’s neighbor, responded via text, “I will tell you unequivocally that I am disappointed that you have fallen in step with the panicky general population.” I retaliated, citing mom’s age (71), her COPD diagnosis and her susceptibility to illnesses in general; as I did my best to assure Tim that I myself was not afraid of becoming ill, nor were the majority of my healthy, able-bodied friends. However, in this particular case, it was not about us.

Mom lives in an off-the-grid, small, forested community in Purdy, Washington. Tim has been a godsend of sorts since moving next door several years prior, providing mom with work that entails taking care of his two Havanese dogs several times a week while he is away – flying helicopters privately for Paul Allen’s international projects for multiple week-long stints (Paul Allen, of course, passed away last year, but Tim’s job has apparently been safe). What’s more, he offered mom a generous $600 monthly sum for these light dog sitting services – the only income she currently receives aside from social security. He purchased a new computer for her at some point, among other things, and provides that rare neighborly support considered to be rather uncommon in the American neighborhoods I’ve come to know personally.

Tim is also a man of staunchly right-leaning ideals. He possesses cold views toward the outside world and, if left unfiltered for long enough, will exclaim certain sentiments that no fellow racist would refute. At one point in our continued phone conversation yesterday pertaining to the bed situation and, consequently, about the virus, he said, “Now this is going to come off as racist…” “Uh-oh,” I thought to myself. “But the Chinese, over there… they’re animals; they eat shit, their infrastructure is shit…” And while Tim carried on, I respectfully listened, patiently, passively, knowing full well, for whatever reason, that I didn’t want to charge back with fury because, well, Tim, a 71-year old aviation mechanic and pilot, is all but set in his ways.

There are certain battles I choose not to fight, particularly with those whom I share some sort of special, unique relationship or bond. Bryan, for instance, who became my Big Brother when I joined the Big Brothers Big Sisters organization in 1995, possesses what I would deem lofty, conservative ideals. Ones that if sparked through conversation would end in anger, arguments, frustration, silence and bitterness. All of this amid the love he possesses for me, wanting to hang out, wanting – in the ways he knows best – what’s best for me, even if “what’s best” for me clearly defies the pillars of his ideological underpinnings. I’ve now known him for 24 years, and we still check up on each other to this day.

Tim, like Bryan, has a soft place – however big, however small – in his heart for both me and for my mom, who is a true bohemian at heart; an airy, unorganized, passionate, forgetful, sensitive, over-thinking, soft-spoken, goofy, utterly kind woman who loves reggae and hip-hop music. Mom never had a long-term plan, neither career-wise nor financially, which has come back to haunt her, us, in this very particular political and financial system we have found ourselves in since moving to America. I have had to ward off resentment over the years as her son, who also struggles financially, who knows that nothing will be left behind or allotted, because that’s what’s expected as we course through this perceived linear journey of money-bearing existence: rewarded with riches or penalized with poverty depending on the infinite possibilities that created us at whatever particular time and place.

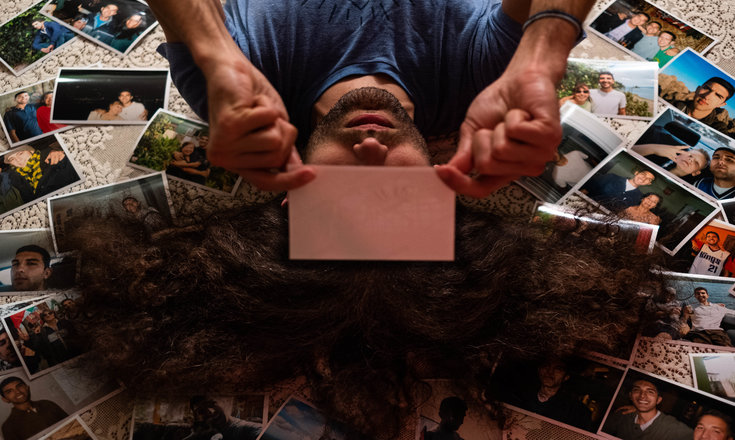

Luke, mom’s son, my brother, was killed in Yemen in 2014, doing what he loved – not in the career sense which also holds true to a large extent, but more so to the degree of consciously living one’s life as a wanderer, unbound from labels, flags, systematic control, the status quo. He was brought into the world in 1981, when mom’s bohemian proclivities were not yet laid to rest, and he was taken in tow to places like Greece, Morocco and Tunisia. And by the time we moved to America from the U.K. in 1988, Luke’s worldly dispositions were firmly rooted in an otherwise dreary apartment complex, lacking in any diversity or culture, in Sacramento, California.

Tim knows about my brother, as many do, and as many more do not. Mom, being his long-time neighbor, couldn’t help but recite Luke’s unfathomably tragic, drawn out story to Tim at various points of their exchanges. She lives alone with her cat and dog (I am her only close family) and her need to release and exude such energy – as is the case for me – amid all the deeply embedded trauma is profoundly necessary. And sadly, when we do unveil such revelations about our lives, our story, Luke’s story, it often falls on disapproving ears; an instantaneous judgement of Luke’s character; a “why would he be there in the first place?” kind of reaction, because all people in that region of the world are lunatics and animals, naturally. So, I make it a point to not conjure up such intense, personal information, or at least choose to be highly selective of those with whom I share.

Thus I leave it be, and ultimately, in the midst of this tumultuous and grief-ridden journey, I heartily contend that We are all in this together, all connected at the hip in the most beautifully poetic of ways. And knowing this, I find it imperative to not win debates with people like Tim; rather, re-shifting the focus to being the most finely crafted instrument of life that I can be, working with what I have, putting up with a suppressive external reality that distracts and deviates me from my true, awe-inspiring, resilient potential (what this is, I continue to seek). Many days, perhaps most, I “fail” in big ways: not showing up, not backing down, eating junk when I know what my body needs, lying around when I know my body requires movement, thinking obsessive thoughts when I know my mind needs to be clear, not sharing my experiences when I know they need to be received; and it’s in times like these, as we experience a global pandemic, when I am reminded of just how important my life, my mom’s life, and those of others, mean to me.

My conversation with Tim became heated, not over his vague bigoted remarks toward China, not toward his remarks about the media sensationalizing COVID-19, but when he insisted that he would have some other individual move mom’s bed if I didn’t do it myself. “This,” I said with a slow-boiling sternness, “defeats the purpose of my not wanting to increase mom’s infection at all. I don’t care about your habits nor your thoughts on the media’s fabrication of coronavirus, but I don’t want anyone jeopardizing mom’s health.” He fought back, saying things like, “your mom is more likely to get a stroke or fall down and hit her head than she is getting the virus.” I cut him off eventually. “Tim! Tim! This is something you cannot quantify, and I’m not talking odds, I am talking risk. I am talking about mom’s life.” She is one of the vulnerable ones. One of the ones we should be protecting, and the one that just happens to be the sweet, old, vibrant woman I call ‘mom.’

Ripple effects. How we treat ourselves and those closest to us should provide an indicator and rule of thumb as to how we treat others we don’t know. “Stranger,” a word that is, in fact, strange and worth dissecting as we as a mass community become collectively enveloped by a global pandemic that, in its resulting nature, reveals just how close – and how distant – we’ve become to one another. Tim’s world views have infiltrated a very small bubble that I call my own when mom suddenly becomes a target of a generalized, hardened naivety. And during these times, from the inside out, my reactions have sparked an emboldened stance – a reminder – of the unity I have with oneself and, in turn, a unity with the source from which we all derive.

Nature doesn’t care. Nature continues to correct itself. Nature is doing exactly what it needs to be doing in the millennia-long wake of human interactions with one another and with this planet. It pains me to distance myself from mom after all we’ve been through, who in her later years needs all the company and positive spirits she can handle. Yet I sit here, 30 miles away from her, writing, lamenting this reality while knowing deep down I wish to celebrate it – all of it; the harshness, the unyielding flow. And when I sit here thinking about mom, and attempt to consider all of those in my circle and beyond, I know that the guilt, the regret, the sorrow, the trauma, is all transcended into little droplets of love, understanding and progress; as difficult as it is to find in Tim, a fixture in mom’s life, and a fixture in the world at large.

Comments are closed.